A Great Inventor and a Great Soul

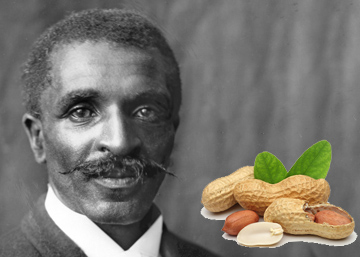

(This is the story of one of the most inspiring and heart-warming unsung heroes, George Carver, a great inventor in agriculture and a great soul. Carver was a pioneer in peanut cultivation in United States, and in the productive utilization of waste products in agriculture. He invented innumerable uses for peanuts and made a myriad of innovations in converting agricultural waste into useful products. He became famous as the ‘Peanut Man’ and an internationally recognized expert in agriculture, specializing in peanuts and agro-waste management. Farmers and industrialists from all over the world came to him for consultation. All the VIPs of America of his times, such as the American presidents Roosevelt, Henry Ford and Thomas Edison, became his close friends. With his inventive genius and connections Carver could have become a billionaire in farming or industry and one of the richest men in the world or secured a high position in government or business. But Carver cared not for money or position. He gave all of his talents and ideas entirely free to whoever came to him for his help or guidance and lived out of a meager monthly salary of $125 dollars, which he received from the institution founded by his last employer and mentor, Booker T. Washington. Washington inspired Carver to give up his comfortable job as a professor and serve a community of poor Black boys. Carver believed that his talents are a gift of God and had to be used for the benefit of people and not for self. His biographer states that Carver “seemed astonished that anyone expected him to claim rewards from the gifts God had given him.”

Carver was extremely different from the most traditional kind of inventors who tend to be eccentric, uneducated, imbalanced, one-sided and self-centered, unsocial and lonely. Carver was a qualified scientist who earned his higher education in agriculture from US universities and went on to work in them as a professor. He was actively involved in community development, mentored poor Black boys and was also an accomplished artist whose paintings were displayed in the famed Luxembourg Gallery in Paris. He was religious, God-centered and unselfish with a passion for serving people and the society. Here are some excerpts from an article on George Carver, excerpted from Reader’s Digest.)

Introducing Carver

Any one of his achievements could have made Carver a man of fabulous wealth. But all his life he refused to accept payment for a single discovery. Actually he had not the slightest regard for money. He never accepted a raise in salary. “What would I do with more money?” he once asked. “I already have all the earth.” Forty years after his arrival at Tuskegee, he was still earning the $125 a month that Washington had first offered him.

Even then, the harried treasurer had to plead with him to cash his paychecks, which were always stuffed in pockets or dresser drawer, so the school’s books could be balanced. When Carver did dig them out, it was usually to give them away. There is no way of knowing the number of boys, white as well as black, whose bills he paid in their time of need. Virtually everyone who knew him remembers at least one such instance.

He was constantly besieged with offers of money from businessmen willing to pay almost any sum for his advice. A group of peanut planters in Florida sent a check for $100 and a box of diseased specimens; if the professor could cure their crop they would put him on a monthly retainer. Carver sent back a diagnosis of the disease, and the check. “As the good Lord charged nothing to grow your peanuts,” he wrote, “I do not think it fitting of me to charge anything for curing them.”

When a dyestuff firm heard that he had perfected an array of substitute vegetable dyes, the owners offered to build a laboratory for Carver, and sent him a blank check. He mailed back the check, and the formulas for the 536 dyes he had found to date. When he declined a princely sum to join another company (which had adopted his process for making lawn furniture out of synthetic marble), the company literally came to him—moving factory and machines to Tuskegee—and got the benefit of his regular counsel at no cost at all.

Thomas Edison once invited him to come and work with him in the Edison Laboratories in Menlo Park, New Jersey, at a minimum annual salary of $100,000. Carver declined the offer, as he had all the others. “But if you had all that money,” he was once challenged, “you could help your people.” “If I had all that money,” Carver replied, “I might forget about my people.”

By now Carver’s reputation had spread across the world, and so much mail poured into Tuskegee—a considerable portion of it addressed simply to The Peanut Man—that the substation of the post office at the Institute was swamped. Some 150 letters a day were dumped on Carver’s desk, and he answered each in meticulous detail. A steady stream of visitors asked to see him, and his door remained open to all. Farmers came to question him about their seeds, townsfolk about their gardens, and boys in the dormitories thought nothing of asking him for help with their homework.

He was, of course, a revered campus character. He often wore the suit he had been given at Ames four decades before, and his neckties, which he knitted from cornhusks, always flaunting the garish colours of whatever dye he happened to be testing. Despite increasing demands on his time, he started a painting class, teaching students to mix an astonishing array of colours from the native clays, and to make canvases from the pulp of peanut shells. And although his genius as an artist had been recognized by the famed Luxembourg Gallery in Paris, where his exquisite work Four Peaches was exhibited, he was quick to give his paintings to anyone who admired them.

Carver’s Solutions

(On how Carver tackled a serious problem in peanut cultivation)

It came this time in the seemingly innocent question of an old woman who knocked on Carver’s door one October afternoon. She was a widow, she told the professor, but she had followed his counsel and turned the farm to cultivate peanuts. There had been a bumper crop, and, after setting aside all the peanuts she could use in the year ahead, she still had hundreds of pounds left over. “Who will buy them?” she asked.

Carver had no answer. He had been so engrossed in breaking the one-crop system, and so successful in promoting the peanut, that almost alone he had created a monster as cruel as the weevil itself. One hasty trip into the countryside, and his blunder glared back at him from every farmyard. Barns were piled high with the surplus, and peanuts were rotting in the field.

He returned racked with guilt, tormenting himself that he had thought the problem only halfway through. Years later, Carver told the story of how, groping for solace, he had walked through the predawn darkness of his beloved woodlands and had cried out,

“Oh, Mr. Creator, why did you make this universe?”

And the Creator answered me, “You want to know too much for that little mind of yours.”

He said, “Ask me something more your size.”

So I enquired, “Dear Mr. Creator, tell me what man was made for?”

Again He spoke to me: “Little man, you are still asking for more than you can handle. Cut down the extent of your request and improve the intent.”

And then I asked my last question. “Mr. Creator, why did You make the peanut?”

“That’s better!” the Lord said, and He gave me a handful of peanuts and went with me back to the laboratory, and together we got down to work.

Inside the laboratory, Carver closed the door, pulled on an apron and shelled a handful of peanuts. That whole day and night, he literally tore the nuts apart, isolating their fats and gums, their resins and sugars and starches. Spread before him were pentosans, legumins, Ivsin, amido and amino acids. He tested these in different combinations under varying degrees of heat and pressure, and soon his hoard of synthetic treasures began to grow: milk, ink, dyes, shoe polish, creosote salve, shaving cream and, of course, peanut butter. From the hulls he made a soil conditioner, insulating board and fuel briquettes. Binding another batch with an adhesive, he pressed it, buffed it to a high gloss, and had a light and weather square that looked like marble and was every bit as hard.

Carver’s Inspiration

(On how Carver was inspired into his mission by his mentor)

In 1896, George received his Master’s Degree in Agriculture and Bacterial Botany. He had never been more content—and yet he was sometimes disturbed by his happiness. He was a Black, and across the land millions of his people starved and stultified, yearning for a place in the sun. Did he serve them best as an example of what a man—any man—could achieve by unending effort? Or did he belong among them, sharing the knowledge he had come by with such labour and pain?

About this time, 1,200 kilometres away in the Alabama town Tuskegee, the acknowledged spokesman of the Black race Booker T. Washington was struggling to achieve his dream of a Black people’s institute of learning. One overwhelming problem confronted him. “These people do not know how to plough or harvest,” he wrote. “I am not skilled at such things. I teach them how to read, to write, to make good shoes, good bricks, and how to build a wall. I cannot give them food.”

Washington became convinced that his most urgent need was someone who could teach his people to farm. He had heard that there was a noted agriculturist, a coloured man, at a school in Iowa, and on April 1, 1896, Washington sat down and wrote him a letter:

“I cannot offer you money, position or fame. The first two you have. The last, from the place you now occupy, you will no doubt achieve. These things I now ask you to give up. I offer you in their place work—hard, hard work—the task of bringing a people from degradation, poverty and waste to full manhood.”

One morning, four days later, as the tall young scientist read the letter, his blood raced and his heart beat fast. God had revealed His plan for George Carver.

When Carver met Washington, he told Carver:

“Your department exists only on paper” and added “Your laboratory will have to be in your head.”

“I will manage,” said Carver.

He set to work.

(Article Courtesy: Compiled and edited from the article ‘Beyond Fame or Fortune’ in Reader’s Digest—75th Anniversary Celebrations: A Selection of Memorable Articles from The Digest, 1922–1997.)

In the first glance, Carver’s attitude to money seems to be ascetic and not in tune with Sri Aurobindo and the Mother’s ideal on the right use of money. Sri Aurobindo and the Mother have said that we should not shun the money-force in an ascetic spirit of denial, but use it with an inner detachment and with an attitude of what the Mother calls as the ‘Will of the Giver’. Carver was not interested in money and he was using his talents and ideas with this attitude of the ‘will of the giver’. These kind of talents and ideas are also a form of wealth. The Sanskrit term ‘Artha’ is translated as wealth. But it also means ‘instrument’ or ‘instruments of wealth’. Inventive talents talent is also a form of wealth, Artha. Carver’s method is perhaps much more direct and effective than that of the businessman–philanthropist. Instead of using his talents to create wealth, and again use this wealth to serve the society, Carver was using his talents directly to help people and serve the society, by passing the stage of money-making. It is also more effective because it frees him from the burden of money and saves the time and energy involved in managing money (for which Carver may not have the temperament or the skill), which can be used more effectively and productively in inventing new things.

We may ask some more questions, such as whether Carver’s approach is in harmony with the highest ideal of charity. Is it not indiscriminate, giving without making any distinction between the rich and the poor or understanding the true needs of the recipients? But such questioning will prevent us from appreciating the sheer beauty of the generosity of his soul and switch off the deep feelings it evokes when we read the story without asking too many questions.

M. S. Srinivasan