Beyond Traditional Environmentalism: An Alternative Paradigm on Environment

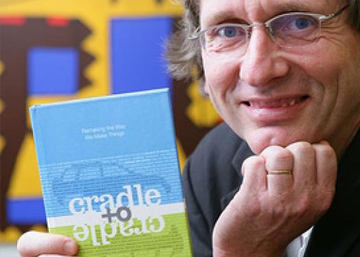

(Review of the book Cradle to Cradle by William McDonough & Michael Braungart, North Point Press)

The remedies to the environmental crisis we are facing today are now more or less accepted by all progressive and thinking minds and getting standardized. They eliminate pollution, consume less, recycle waste, minimize the use of non-renewable resources. Here are two people, an architect and a chemist, who dare to question this accepted environmental wisdom—which looks very reasonable—and offers a better and alternative paradigm for dealing with the ecological crisis facing our humanity.

The authors of this book under review William McDonough and Michael Braungart take a sharp, critical look at the present standardized remedies suggested for restoring our damaged environment, for example, recycling. But what is interesting and valuable in this book by McDonough and Braungart are not their criticism but their positive, wider and enriching vision and approach to environmentalism.

William McDonough is an architect and the principle founder of ‘William McDonough and Partners, Architecture and Community Design’, based in Virginia. Time magazine recognized him as a ‘Hero for the Planet’. In 1996, he received the Presidential Award for Sustainable Development, the highest environmental honour given by the United States. Michael Braungart is a chemist and the founder of the Environmental Protection Encouragement Agency (EPEA) in Hamburg, Germany. Prior to starting EPEA, he was the director of the chemistry section of Greenpeace.

The Cradle to Grave Model

The title of the book is based on two contrasting models of development. The first one, the traditional industrial model, where things are made, used and discarded is the ‘cradle to grave’ model. McDonough and Braungart present a ‘Cradle to Cradle’ model where the discarded things, what we call as waste, become the cradle for something useful or enriching. The traditional environmentalism offers recycling as the remedy for waste. But Macdonough and Braungart indicate the defects in this method which are unrecognized in most of the discussion on it. As they point out:

“Just because a material is recycled does not make it ecologically benign, especially if it was not designed specifically for recycling. Blindly adopting superficial environmental approaches without fully understanding their effects can be no better – and perhaps even worse – than doing nothing.”

When a product is not predesigned for recycling, it may happen that one set of harmful chemicals are replaced by another equally harmful ones used in the process of recycling. McDonough and Braungart give many examples for illustrating these defects of recycling. Here is one of them:

“In some developing countries, sewage sludge is recycled into animal food, but the current design and treatment of sewage by conventional sewage system produce sludge containing chemicals that are not healthy food for animals. Sewage sludge is also used as fertiliser, which is a well-intentioned attempt to make nutrients, but as currently processed it can contain harmful substances (like dioxins, heavy metals, endocrine disrupters, and antibiotics) that are inappropriate for fertilising crops. Even residential sewage sludge contains toilet paper, made from recycled paper, may carry dioxins. Unless materials are specifically designed to ultimately become safe food for nature composting can present problems as well.”

The Cherry Tree Paradigm

But the more positive part of the book is that the authors provide a much more enriching alternative to the current thinking on environment. According to McDonough and Braungart, contemporary environmentalism based on the principle of ‘reduce, reuse, recycle, – and regulate’ impoverishes Nature and life and it is contrary to the ways of Nature, which produces a creative, diversified and beautiful abundance. The true Environmentalism has to follow this richer ways of Nature. The authors of this book frequently cite the cherry tree as the example of their alternative approach. “Consider the Cherry tree: thousands of blossoms create fruit for birds, humans and other animal, in order that one pit might eventually fall onto the ground, take root, and grow,” say the authors, and elaborate further on the way of the cherry tree:

“The tree makes copious blossom and fruit without depleting the environment. Once they fell on the ground their materials decompose and break down into nutrients that nourish microorganisms, insects, plants, animals and soils. It enriches the ecosystem, sequestering carbon, producing oxygen, cleaning air and water, and creating and stabilising soil. Among its roots and branches and on its leaves, it harbours a diverse array of flora and fauna, all of which depend on it and on one another for the functions and flows that support life. And when the tree dies, it returns to the soil, releasing as it decomposes, minerals that will feed healthy new growth in the same place … what might the human-built world look like if a cherry tree had produced it.”

Inspired by the example of the cherry tree, the authors of this book offer an alternative model of environmentalism where products can be designed in such a way that after their useful lives they will become either ‘biological nutrients’ which re-enter the cycles of Nature and the water and the soil without injecting synthetic materials or toxins into it or else they become ‘technical nutrients’ which continually circulate within the industrial cycles as useful materials or products.

Eco-efficiency and Eco-effectiveness

McDonough and Braungart make a clear distinction between ‘eco-efficiency’, which is the main principle of current environmentalism, and ‘eco-effectiveness’, which is the principle of the new paradigm that they offer as the better alternative. The main features of the eco-efficiency model are:

- Release fewer pounds of toxic wastes into the air, soil and water every year.

- Measure prosperity by less activity.

- Meet the stipulation of thousands of complex regulations to keep people and natural systems from being poisoned too quickly.

- Produce fewer materials that are so dangerous that they will require future generations to maintain constant vigilance while living in terror.

In contrast, the eco-effectiveness model is based on the following principles:

- Buildings which, like trees, produce more energy than they consume and purify their own waste water.

- Factories that produce affluent that are drinking water.

- Products that when their useful life is over do not become useless waste but can be tossed into the ground to decompose and become food for plants and animals and nutrients for soil; or alternately that can return to industrial cycles to supply high-quality raw materials accrued for new products.

- Billions and trillions of dollars’ worth of materials accrued for human and natural purposes each year.

- Transportation that improves the quality of life while delivering goods and services.

- A world of abundance, not one of limits, pollutions and worse.

This is not merely a utopian theory. Drawing from their rich experience in environmental consulting, the authors give many examples on how they redesigned things from carpets to corporate campuses. Let us look at one example, described by the authors:

“Working with a team assembled by Professor David Orr of Oberlin College, we conceived the idea for a building and its site modelled on the way a tree works. We imagined ways that it could purify the air, create shade and habitat, enrich soil, and change with the seasons, eventually accruing more energy than it needs to operate. Features include solar panel on the roof; a grove of trees on the building’s north side for wind protection and diversity; an interior designed to change and adapt to people’s aesthetic and functional preference with raised floors and leased carpeting; a pond that stores water for irrigation; a living machine inside and beside the building that use a pond full of specially selected organism and plants to clean the effluent; classrooms and large public rooms that face west and south to take advantage of solar gain; special windowpanes that control the amount of UV light entering the building; a restored forest on the east side of the building; and an approach to landscaping and grounds maintenance that obviates the need for pesticides or irrigation. These features are in the process of being optimized – in its first summer, the building began to generate more energy capital than it used – a small but hopeful start.”

On another assignment, a textile manufacturing company asked the authors to redesign a fabric which was producing toxic effluent and it was done in such a way that effluents are cleaner than the water that went in! The environmental inspectors were baffled and wondered whether their testing instruments were working properly!

The Larger Crisis

This brings us to the question whether the eco-efficiency model can be entirely abandoned? The authors admit that eco-efficiency is helpful as “transitional strategy to help currents system to slow down and turn around”. However, the authors do not address serious environmental problems posed by a predominantly consumerist culture, when it starts consuming limited, non-renewable resources on a large scale with a ravenous appetite. Asia in general and large populous countries such as India and China are facing such a crisis. As Kishore Mahubhari, former Singapore Ambassador to UN describes the crisis facing Asia:

“Two virtually certain major trends will create a massive global collision. First, Asian living standards will rise spectacularly. This is good. Second, Asian will replicate Western consumption patterns. This is bad. How do we gain the good and avoid the bad? This will be one of the biggest questions of the twenty-first century.”

In such situations, a strategy based on the principles of eco-efficiency with restraints and limits to consumption of resources seem to be the right remedy. Chandran Nayar, the founder of the Global Institute for Tomorrow, in his book Consumptionomics, presents a blueprint for tackling the Asian environmental crisis based predominately on the principle of eco-efficiency. Writing about the main cause of the environmental crisis, Nair says: “That cause is what we consume – both its volume and its nature. The only way the world can expect to have an environment fit for those currently alive to live in, and to pass on the future generation in a decent form, is by consuming less and in a different way.”

The much-talked about ‘demographic dividend’ of a large population can be realized only when we are able to provide the basic needs of the population and make each individual into a productive citizen with sufficient health, education and skill. All these require immense amount of resources and how to find it? Assuming we are able to harness these resources and create a productive population, when a large part of this population rises in the economic pyramid and takes on to the western types of consumption in the form of more and more TVs, cars, fridges, etc., then will it not become a too heavy burden for the environment? So, reducing excessive consumption of resources is something indispensable for preserving the environment, and the need for controlling the population cannot be dismissed or underestimated.

This brings us to in other important environmental concern – population growth. But the authors of this book do not offer any useful strategies on how to tackle this problem in an ‘Eco-effective’ way. They are highly critical of the reduce–minimize–avoid culture of traditional environmentalism which counsels “we must shrink our presence, our systems, our activities and even our population control through limiting birth rates as the most effective way to deal with the problem”. The authors of this book are critical of this approach but do not offer any better alternative.

How to bring down consumption? There are the outer or material methods through regulation, laws, environmental education and many others. But there is also an inner, psychological path. The driving force behind consumption is desire for more and more material objects or enjoyments and reduction or renunciation of this kind of desires can lead to reduced consumption. The best way to do it is to turn the energy of desires towards non-material objects, which aims fulfilment in the intellectual, aesthetic or spiritual realms. So a system of education which awakens this higher needs or the aspiration of these higher aims can help not only in spiritual growth but also beneficial to our environment.

M. S. Srinivasan