Changing Paradigms of Innovation: Orbit-Shifting Innovators

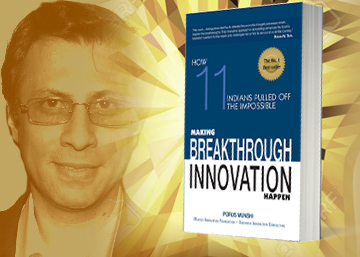

(Review of the book Making Breakthrough Innovation Happen by Porus Munshi, HarperCollins Publishers India)

At the rate that technology, product and service ranges and human thought-processes are evolving, there is a growing consensus among corporate leaders and gurus that in the future world ‘Innovation’ holds the key to competitive advantage, for companies, communities as well as for nations. However, among foremost pioneering nations, India is never regarded as a great innovator. India is more known for jugaad—quick-fix improvisations—than for lasting and breakthrough innovations.

In this book, Making Breakthrough Innovation Happen by Porus Munshi (which is described by R. Gopalakrishnan, former Executive Director of TATA Sons, as a ‘must-read work of great inspiration’), the author dispels this notion by presenting the case studies of 11 Indian companies and institutions which ‘pulled off the impossible’ by making what he calls as ‘orbit-shifting innovations’. The author is a management consultant and a partner at Erehwon Innovation Consulting, a company dedicated to fuelling innovation in India.

Porus Munshi takes a different and deeper approach to the subject of innovation from the traditional ones which try to arrive at some general or universal principles or bring out a to-do list from the outer behaviour or practices or process of successful innovators.

In this book Munshi tries to understand the mindset and thought process of orbit-shifting innovator. He quotes Dr Natchiar of Arvind Eye Hospital, “We keep sharing our best practices, process and methods with other organizations … but none of them is able to replicate what we do because they focus on the process and not on the underlying philosophies that drive the organization.” She comments further: “Really the internal leads the external. As long as we focus on the external manifestation and not on the internal mind-sets and beliefs that drive orbit-shifting innovations we are going to be focusing on wrong things and true replication won’t happen.” This is very much in harmony with the Indian spiritual ethos which emphasizes on the principle of ‘from within outwards’ as the foundation of all effective action or creation.

Porus Munshi identifies four major tasks in achieving orbit-shifting innovation. First is a Mission Impossible, an extremely challenging mission. Second is to arrive at a breakthrough strategy to reach the mission. Third is to form a team which believes in the mission and convinced it can be done. Fourth is to enrol all the stakeholders and infect them with their mission.

Here are some of the companies and institutions among the 11 breakthrough innovators:

- Dainik Bhaskar newspaper which was able to achieve No. l circulation from the first day, wherever they launched it, in a market with reputed newspapers with a large circulation.

- Titan which came out with the slimmest, water-resistant watch in the world, which even the Swiss were not able to produce.

- Shanta Biotech which developed a low-cost Hepatitis Bvaccine and ushered in the biotechnology age in India.

- Trichy Police which rewrote policing programmes and created an innovative community policing system

Let us briefly look at the mission and strategies of the first and the fourth examples, Dainik Bhaskar and Trichy Police. The newspaper company Dainik Bhaskar first launched its paper in Jaipur with a mission of becoming No. 1 or 2 in circulation from day one. The company leadership discarded the traditional market surveys and aimed at in-depth understanding of the readership patterns and the needs of the readers by meeting a whopping 200,000 potential newspaper-buying households in Jaipur. They decided to evolve the product (in this case the newspaper) according to the customer needs. They went to each customer and asked him/her questions such as: “What are you not getting in the current newspaper that you would like to get more of” and “What should your newspaper do for you to make you more satisfied?” Then, based on the feedback, the survey team went back to all 200,000 households to show them what they had created, based on their feedback. A large army of fresh college students and graduates were deployed by the company to accomplish this huge task. They were formed into many small groups with a supervisor. Every day in the morning they went to work energized by a silent prayer to God and followed by a brief session of singing of inspiring or patriotic songs. Without entering into any more details of the strategies of Dainik Bhaskar, what we have tried to present here is a glimpse of the orbit-shifting thinking of the innovator.

Most of the innovations described in this book are product innovations. Among the category of service innovation, there is the case study of the famous Arvind Eye Hospital which is too well known to be retold. However, there is another remarkable case study which is not well known and goes beyond the product–service category of a true social transformation of the community. It is the case of a unique and highly innovative community policing model, conceived and implemented with admirable effectiveness by a police commissioner, J. K. Tripathy, in Trichy, a town in Tamil Nadu.

Porus Munshi describes the achievement of this great leader in the following words:

“Within two years of Tripathy’s taking over, Trichy had been transformed. As many as 261 dreaded criminals were nabbed and the crime rate dropped by about 40 per cent, an eventuality until then considered impossible. For, it was thought that crime could only increase, or at best be contained, but that it could not drop. Today, a decade later, Trichy is a city at peace and a lighthouse of communal amity. Public–police relationships are at a scale unprecedented for India. Policemen are called ‘anna’ [brother] not out of fear but out of respect and regard. They get invited to functions and marriages. All the stakeholders—community, police, politicians, bureaucrats and NGOs—work together in considerable harmony. And more importantly, for a city seething with communal anger prior to 1999, there have been no incidents of communal violence since. The police have become an integral part of the community, and this isn’t some ‘advanced’ Western country we are talking of. It has happened right here in India, in less than two years and has been sustained for a decade.”

Let us look briefly at how Tripathy was able to achieve this extraordinary result. The police force is one of the most rigid and traditional organizations, in which power and authority is concentrated at the top and wielded with a severe firmness. Tripathy changed it radically by delegating the freedom, power and authority to the frontline constables at the lowest levels. For implementing his unique community police model, Tripathy handpicked 260 constables on the basis of internal police records. He picked those with no record of corruption, bad habits and with a track record of effectiveness. The constables were called ‘beat officers’ and groups of four were responsible for a locality. They were told that the beat (area/locality) was their baby completely and that they were responsible for it in every way. They could take whatever decisions they required without consulting their superiors or supervisors. They could do whatever they thought was best.

The other unique achievement of Tripathy is that he was able to convince the beat officers that their responsibilities include not only crime-busting but also to help people in the zone in solving their individual and community problems, for example issues with the ration card, water supply, fixing street lights, finding trained and authorized plumbers and electricians. The residents of the community began giving their applications for water, sewage and telephone connections to the beat officers and these were taken up with the commissioner. When the municipality officials complained that the police were overstepping their authority and interfering into their domains, Tripathy told them bluntly: “You are corrupt and take bribes from the people to do your work. We want to serve people honestly. If you do your work honestly we will not interfere.”

Tripathy made arrangements for the beat officers to talk through television and radio programmes about their work and what they are trying to achieve through the unique community policy model. This was a great boost to their motivation. Where on the earth do ordinary constables at the lowest levels of police hierarchy allowed to present their thoughts on TV and radio? Under Tripathy’s leadership, the relationship between police and people became so friendly and intimate that they are affectionately referred by people as ‘Anna’ (or elder brother) and the beat officers were invited by people for weddings and social functions as special guests. Tripathy was able bring about a transformation in police–community relationship which is unique and rare.

I have described this case study of Tripathy in some detail because it is this kind of innovation and leadership which can create the future world. Product innovations are important for the corporate world, but what is much more important for creating a new and better world in the future are innovations which lead to the higher evolution of the community through the realization of a more holistic, inclusive and humane concepts and values, such as what Commissioner Tripathy was able to achieve.

This book by Porus Munshi, written in an easy and engaging style, is insightful and inspiring. It provides broad guidance to leaders and entrepreneurs, without becoming narrowly preachy on the nature of the thinking process which can lead to breakthrough innovation.

M. S. Srinivasan