The Business Ethics of J.R.D. Tata

The life of JRD Tata defines ethics and values in their truest sense showing us that it is possible to create a large, successful and yet humane organization.

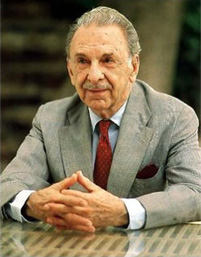

JRD Tata was the Chairman of Tata Sons, the holding Company of the Tata Group of Companies which has major interests in Steel, Engineering, Power, Chemicals and Hospitality. He was famous for succeeding in business while maintaining high ethical standards. Under JRD’s Chairmanship, the number of companies in the Tata Group grew from 15 to over 100. Monetarily, the assets of Tata group grew from Rs 620 Million to over Rs 100 Billion.

In the public mind, ethics in business is mainly identified with financial integrity. Important as that is, the real meaning of ethics goes beyond that. The dictionary defines it as “the science of morals in human conduct, a moral principle or code.” It encompasses the entire spectrum of human conduct. Business ethics lays down how a person in business deals with his or her colleagues, staff and workers, shareholders, customers, the community, the government, the environment and even the nation at large.

J.R.D. Tata was meticulous when it came to financial ethics. When I pointed out to him in 1979 that the Tatas had not expanded as much in the 1960s and 1970s as some other groups had, he replied: “I have often thought about that. If we had done some of the things that some other groups have done, we would have been twice as big as we are today. But we didn’t, and I would not have it any other way.”

The well-known tax consultant, Dinesh Vyas, says that JRD never entered into a debate over ‘tax avoidance’, which was permissible, and ‘tax evasion’, which was illegal; his sole motto was ‘tax compliance’. On one occasion a senior executive of a Tata company tried to save on taxes. Before putting up that case, the Chairman of the company took him to JRD. Mr. Vyas explained to JRD: “But sir, it is not illegal.” JRD asked, softly: “Not illegal, yes. But is it right?” Mr. Vyas says that during his decades of professional work no one had ever asked him that question. Mr. Vyas later wrote in an article: “JRD would have been the most ardent supporter of the view expressed by Lord Denning: ‘The avoidance of tax may be lawful, but it is not yet a virtue.’”

Attitude to Colleagues

When he rang us in the office he would first ask: “Can you speak?” or “Do you have someone with you?” Except when he was agitated, he would never ask you: “Can you come up?” He was always polite.

JRD’s strong point was his intense interest in people and his desire to make them happy. Towards the end of his life he often said: “We don’t smile enough.” When I was writing The Creation of Wealth, he told me about his dealings with his colleagues: “With each man I have my own way. I am one who will make full allowance for a man’s character and idiosyncrasies. You have to adapt yourself to their ways and deal accordingly and draw out the best in each man. At times it involves suppressing yourself. It is painful but necessary…. To be a leader you have got to lead human beings with affection.”

It is a measure of his affection that even after some of them retired he would write to them. He was always grateful and loyal. To him, ethics included gratitude, loyalty and affection. It came about because he thought not only of business but also of people. In dealing with his workers he was particularly influenced by Jamsetji Tata, who at the height of capitalist exploitation in the 1880s and the1890s gave his workers accident insurance and a pension fund, adequate ventilation at the workplace and other benefits. He wanted workers to have a say in their own welfare and safety, and he wanted their suggestions on the running of the company. A note that he wrote on personnel policy resulted in the founding of a personnel department. As a further consequence of that note came about two pioneering strokes by Tata Steel: a profit-sharing bonus and a joint consultative council. Tata Steel has enjoyed peace between management and labour for 70 years.

Beyond Business

Decades later, Tata Steel workers had received several benefits. Then JRD looked further.

In a speech in Madras in 1969 he called on the managements of industries located in rural or semiurban areas to think of their less fortunate neighbours in the surrounding regions. “Let industry established in the countryside ‘adopt’ the villages in its neighbourhood; let some of the time of its managers, its engineers, doctors and skilled specialists be spared to help and advise the people of the villages and to supervise new developments undertaken by cooperative effort between them and the company.”

To put JRD’s ideas into action, the Articles of Association of leading Tata companies were amended and social obligations beyond the welfare of employees was accepted as part of the group’s objectives. In the 19th century, Baron Edward Thurlow, the poet, asked: “Did you ever expect a corporation to have a conscience?” The answer from J.R.D. Tata was: “Yes”.

Whenever he could, he raised his voice against state capitalism. He never bent the system for his benefit. L.K. Jha recalled in 1986 that whenever JRD came to him when he was a Government Secretary, he came not on behalf of a company but the whole industry. He wanted no favours, only fairness.

In his last years he was very conscious of the environment and industry’s part in spoiling it. He wrote in his Foreword to The Creation of Wealth in 1992: “I believe that the social responsibilities of our industrial enterprises should now extend, even beyond serving people, to the environment.”

The J.R.D. Tata Centre for Ecotechnology at the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation was created in furtherance of his desire.

To him India was not a geographical expression; it was people. When he was awarded the Bharat Ratna in 1992, Tata employees arranged a function on the lawns of the National Centre for Performing Arts in Mumbai. A gentle breeze was blowing from the Arabian Sea. When JRD rose to speak, he said: “An American economist has predicted that in the next century India will be an economic superpower. I don’t want India to be an economic superpower. I want India to be a happy country.”

This was not only his hope, it was also his life. He brought sunshine into the lives of many of us who knew him

Russi M. Lala was the director of Tata’s premier foundation – The Dorabji Tata Trust for eighteen years. His book ‘The Heartbeat of a Trust’ is based on this Trust. He has authored a large number of books including ‘Beyond the Last Blue Mountain: A Life of JRD’. He is also co-founder of the ‘Centre for the Advancement of Philanthropy’ and has been its chairman since 1993.

R.M. Lala